These days, I am working on Rachmaninoff’s Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (a.k.a. the “Rach 3”), as I prepare for performances of it in February and March.

The more I delve into this concerto (composed in 1909), the more I realize that, out of the many challenges the work presents, perhaps the most difficult one lies in its many transitions. I am striving to play the whole piece as a unit, organically quickening or slowing its pulse according to the Composer’s speed- and character-related markings. It is not that easy, but I think it is more important than taking off as soon as Rachmaninoff writes “poco piú mosso”, or some similar marking, thus using faster sections only to display technical prowess. They must be strictly related to the slower sections, I believe. There are plenty of example of this, basically at every indication of “piú mosso”, “poco piú vivo”, etc.

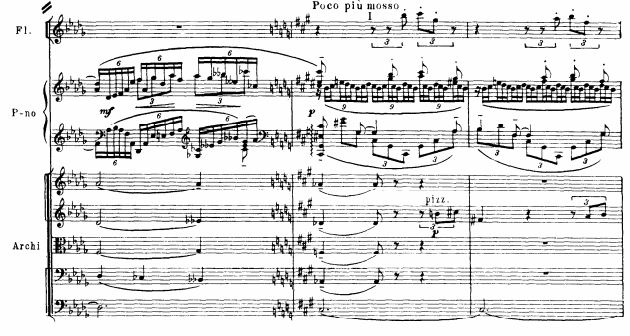

A particularly good example is the “Poco piú mosso” in the second movement, after the climax (following rehearsal figure 32 in the Boosey & Hawkes edition).

I have heard this concerto (dedicated to Josef Hofmann) played too many times, even by excellent pianists, in a way that made me feel that it was too fragmented, compartmentalized, and that many sections felt like unattached limbs, and did not fit the whole. I believe that every part of this concerto comes as a direct consequence of either the immediately preceding one, or several of the preceding ones, as a cumulative effect. It is a wonderful narration, with many psychological subtleties and some major cathartic moments.

I’ve decided to play the “other” cadenza instead of the massive one that is perhaps more popular nowadays. At first, Rachmaninoff wrote the one known as the “ossia”, and then composed a second one. The composer himself chose to play this “leaner” cadenza in his 1939 recording of the piece. [at exactly 9:00” in the following recording]:

I learned the “ossia” first, not even considering the other one (perhaps I was under the spell of Van Cliburn’s recording with Kondrashin, which to me remains unmatched). [at 10’49” in the following video]:

Then, slowly but surely, I started feeling the need for some relief from the chordal writing so prominent in the movement, and in the concerto. I believe this may very well be the reason why Rachmaninoff wrote the second version of the cadenza, where the soloist has single-note runs like nowhere else in the movement, and instead of thick, massive chords and wide jumps, lean ones that skip nervously about. After a while the two cadenzas become one and the same, reaching again incredible levels of concentration through thick chordal passages that seem to have the same gravitational force of black holes.

Just the other day I watched a Video Artists International DVD with footage from 1956, in which pianist Aldo Ciccolini, whom I was lucky to have as a teacher for a couple of years, interprets the first movement of Rach 3. I wish the other movements had been included, as well! It is a great performance, and very different from the best known recordings of this work. Ciccolini played the “leaner” cadenza. So did Martha Argerich, as well as many others. I think it is the right choice. I hope my audience will concur!